Soil is a living membrane. A complex and vibrant ecosystem that conventional agricultural farming methods destroy.

Industrial farming relies on fossil-fuel-intensive chemical fertilizers and pesticides, pollutes waterways, and increases soil erosion.

There is an alternative.

“The land that my father has given me, I hope to be able to pass on to my children in good condition, so that they can pass it on to future generations and that for them it will be even better than when I received it.”

Organic farming refers to a system of production that does not use synthetic chemicals and, instead, mimics natural systems. This may encompass different farm sizes, practices and philosophies that, at their core, reject the use of toxic, synthetic chemicals.

Organic Farming Philosophy.

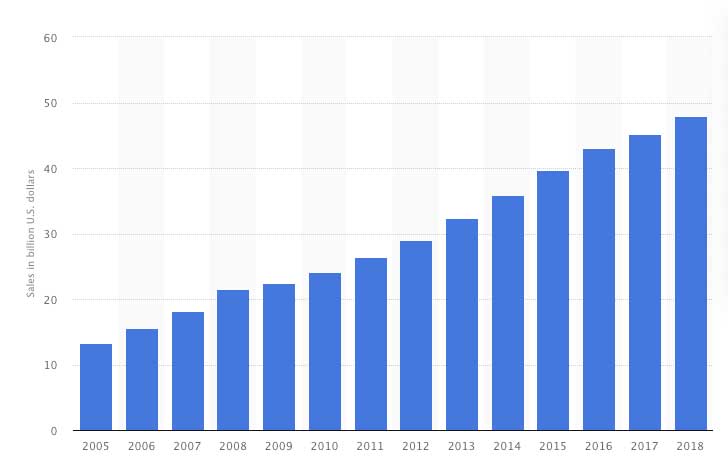

Organic food sales have doubled in the last decade, but organic farming in the United States has not kept pace.

The United States is one of the world’s top producers and exporters of organic corn and soybeans, but imports of these crops increased by 337% and 127% percent respectively between 2012 and 2016 due to domestic demand.

The United States does not have enough organic farms.

Why not?

The Double Bind

Take a step back from the complexity, from the moving parts of modern farming, and bring it back it one simple truth.

Soil turns organic matter into nutrients. Nutrients grow food, food that helps maintain and grow our bodies, as well as supporting life on this planet.

During this process, plants use up the nutrients in the soil, nutrients that have to be replaced to maintain the health of the soil, the corollary of which is to maintain the health of not just human life, but all life on our planet.

Conventional farmers are caught in a double bind.

Of paying more to earn less, while simultaneously decreasing the reproductive nutrients in the soil, funding shortfalls by leveraging assets, to pay more for fertilizers, while not reducing carbon emissions by using more energy, to earn less at market.

Painting Into a Corner

Between 2012 and 2017 net cash income of producers is down from $78,553,368 in 2012 to $65,795,218 in 2017, a fall of $12,758,150.

$78.55 million in 2012 is, normalizing to account for the drop in the purchasing power of the US dollar, the equivalent of $83.86 million in 2017.

This means, in terms of dollar purchasing power, producers in 2017 are making 23% less than they were in 2012.

Commodity prices for conventional crops are frequently below the cost of production, making it impossible for farmers to improve their situations.

“Get big or get out” is the mantra and the only way to survive. Farms consolidate. Families are displaced. Young people, seeing no future in farming, migrate to cities.

Cropland accounted for 44 percent of all US farmland in 2017, while permanent pasture and rangeland accounted for 45 percent. As cropland shifted to larger operations between 1987 and 2017, pasture and rangeland moved the other way, shifting away from the largest farms and ranches toward smaller operations. Farms and ranches with 10,000 acres or more of pasture and rangeland held 43 percent of the total farm and ranch acreage in 2017, down from 51 percent in 1987, with most of the land moving to farms and ranches with less than 500 acres.

The Squeeze

To maintain production yields and profit margins, conventional farmers turn to automation and herbicides like Glyphosate and Dicamba. Dicamba is a selective broadleaf weed killer. Glyphosate kills everything.

Both are bad.

Automation is hollowing out communities as jobs are lost, and while the result is another crop delivered, the cost is being paid in the quality of the soil.

And, to make this balancing act pay, more and more conventional farmers are borrowing against their land.

Increased mechanization, the destruction of farming communities, and the ruination of the soil, all paid for with borrowed money, and, as the leveraged borrowing continues, is there a crisis in farming? — one way to know something is not quite right is when you have a suicide line setup exclusively for farmers.

The Organic Solution

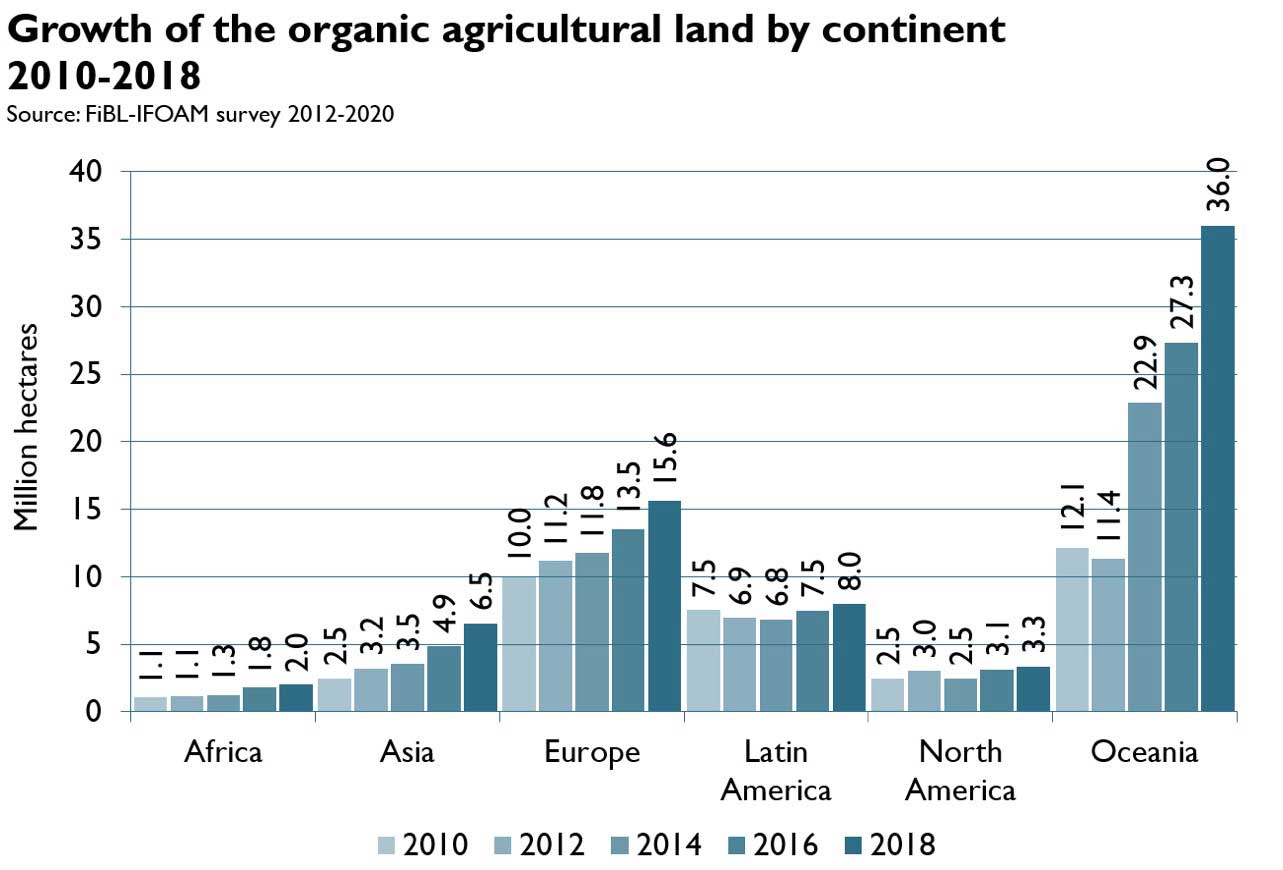

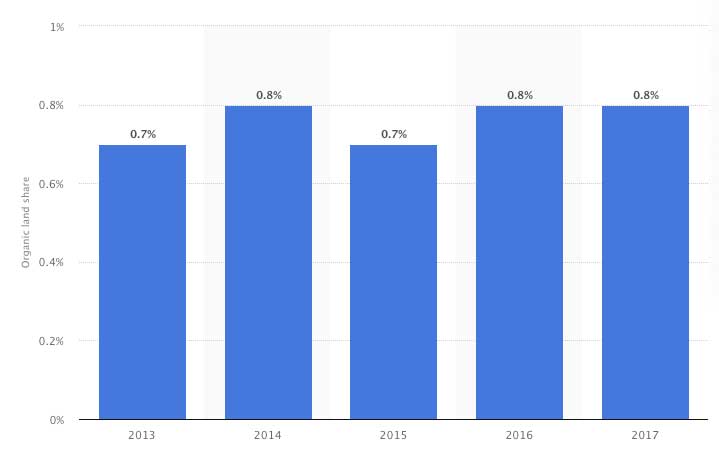

Organic product sales have climbed by over 276% since 2005, with demand outstripping supply, yet between 2013 and 2017 less than 1% of all US farmland is certified organic.

Government subsidies for conventional farmers reduce the overall cost of conventional crops. Equal subsidisation is not yet available to organic farmers, making organic farming more expensive because it is more labour intensive and because of the higher cost of organic feed.

Consumers are prepared to pay more upfront for an organic product, but society pays, both literally and metaphorically, for conventional agriculture’s unintended consequences including eroded soils, polluted water, and a farmer suicide crisis.

Real World Testing

In a trial beginning in 1981, the Rodale Institute’s Farming Systems Trial is the longest-running side-by-side comparison of organic and conventional grain cropping systems in North America.

Rodale used corn and soybean production because these two crops make up the largest percentage of total cropland in the US.

Rodale’s decades-long research has shown organic systems:

- Are competitive with conventional yields after a 5-year transition period.

- Produce yields up to 40% higher in times of drought.

- Earn 2-6X higher profits for farmers.

- Leach no toxic chemicals into waterways.

- Use 45% less energy.

- Release 40% fewer carbon emissions.

Farming Systems Testing

The Rodale Institute Farming Systems Trial, starting in 1981, consists of three systems: organic manure, organic legume, and conventional.

The Farming Systems Trial was designed to assist farmers looking to transition from conventional to organic and is intended to yield useful data. Rodale utilizes an advisory board of farmers from around the country who make sure the methods are consistent with contemporary practices.

Rodale analyses grain cropping systems because 70% of crops grown in the United States are grains, including corn, soy, oats, and wheat.

The Rodale Farming Systems Trial is intended to be a model of standard agricultural techniques, so GMO crops and no-till were introduced to the conventional plots in 2008 when their use became widespread across the country.

The Rodale Farming Systems Trial is a long-term study by intent. Short-term studies that take place over only a few years can’t measure longer-term weather effects, like drought, that will inevitably occur, or biological changes to the soil, which can happen slowly. Farmers need long-term studies to understand real solutions to problems affecting the future of global food production.

Each of the three systems is further divided into two: tillage and no-till.

No-till and organic no-till are not created equal.

Myth Buster: Conventional no-till utilizes herbicides to terminate a cover crop, whereas organic systems use tools like the roller-crimper. Rodale have found that organic no-till practices year after year do not yield optimal results, so Rodale’s organic systems utilizes reduced tillage. The ground is ploughed only in alternating years.

The Three Main Test Systems

Organic Manure

This system represents an organic dairy or beef operation, utilizing a long rotation of annual feed grain crops and perennial forage crops. Fertility is provided by leguminous cover crops and periodic applications of composted manure. A diverse crop rotation is the primary line of defense against pests.

Organic Legume

This system represents an organic cash grain system. It features a mid-length rotation consisting of annual grain crops and cover crops. The system’s sole source of fertility is leguminous cover crops, and crop rotation provides the primary line of defence against pests.

Conventional Synthetic

This system represents a typical US grain farm. It relies on synthetic nitrogen for fertility, and weeds are controlled by synthetic herbicides selected by and applied at rates recommended by Penn State University Cooperative Extension.

Each of the three main systems is further divided into two: Till and No-Till.

Note: Tillage

Each of the major systems was divided into two in 2008 to compare traditional tillage with no-till practices. The organic systems utilize Rodale’s innovative no-till roller/crimper, and the no-till conventional system relies on current, widespread practices of herbicide applications and no-till-specific equipment.

Crop Rotation

The crop rotations in the organic systems are more diverse than in the conventional systems, including up to seven crops in eight years (compared to two conventional crops in two years). This means that conventional systems produce more corn or soybeans because they occur more often in the rotation, but organic systems produce a more diverse array of food and nutrients and are better positioned to produce yields, even in adverse conditions.

Genetically Modified Crops

According to the Department of Agriculture, 94% of all soybeans and 72% of all corn currently grown in the United States are genetically modified to be herbicide-tolerant or show pesticides within the crop.

In 2008, genetically modified (GM) corn and soybeans were introduced to the Farming Systems Trial to represent agriculture in America. GM varieties were incorporated into all the conventional plots.

Results

Here are the results from the first 30 years of comparing corn and soybean organic production to conventional farming methods:

(After a three year transition period)

- Over thirty years, organic yields were the same as conventional yields in terms of pounds per acre per year in the tilled systems.

- But, overall, the profits from the organic systems were 193% higher than the conventional systems.

- The organic systems used 28.5% less energy and emitted 35.3% fewer greenhouse gases in terms of pounds of CO2 per acre per year.

- Organic corn yields were 31% higher than conventional in years of drought.

- Corn and soybean crops in the organic systems tolerated much higher levels of weed competition than the corn and soybeans grown using the conventional system. This is significant, given the rise of herbicide-resistant weeds in conventional systems, and also highlights the much-improved health and productivity of organic soil which can support crop yields that match the conventional system despite the weeds.